Anyone but her husband: Roberta Findlay revisited

Trigger warning: following text contains a representation of sexual violence.

Between 1966 and 1989, Roberta Findlay directed, wrote, produced, shot, edited, and occasionally acted in countless exploitation, horror, and pornographic films, often under pseudonyms or in production contexts where the precise nature of her involvement was unclear (and subsequently obfuscated by Findlay’s own shifting stories on the subject). At her company Reeltime, she also managed the distribution of many of these works across North America and, at least to some extent, in foreign territories, first for her adult work and then, between 1985 and 1988, for the cheap horror and exploitation films she made with the VHS market in mind. Despite this considerable and quite singular oeuvre, Findlay remains an elusive character whose films and pugnacious public comments thwart the tidy auteurist and especially feminist readings well-meaning fans apply to them.

As Findlay is happy to brutishly insist whenever anybody asks, she was a commercial opportunist who only made “dirty movies” because they were fast and cheap and because she wanted to make as much money as quickly as possible. She will admit she took a measure of pride in her lighting and editing, but otherwise stresses that she only made the films for cash and gave up on the business as soon as they ceased to turn a profit. She hated shooting sex scenes, reportedly giving such pithy on-set direction as “Okay, everybody screw”.[1] She insisted that she always refused to hire women for her films because of their apparent physical (and mental) weakness, despite once working as cinematographer on Karen Sperling’s pioneering feminist film The Waiting Room (1973),[2] whose crew consisted entirely of women two years before Chantal Akerman insisted on the same for Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). She continues to scorn anybody who watches her films today as “sick” and is known for hanging up on interviewers who try to contact her. But she was also trained as a classical pianist before she left home at 16 to make films with Michael Findlay, of whom her Hungarian-Jewish immigrant parents disapproved, and has repeatedly said that her dream project is an adaptation of Herman Melville’s Pierre; or, The Ambiguities (1852). And there are crucial moments in her films when her personality – sardonic but artistically ambitious – is unmistakably evident: Mystique (1980), a mournful X-rated film about a dying woman seduced, brutalised, and humiliated by a much younger female lover, opens with a poem by Paul Valéry, while Anyone But My Husband (1975) begins with a montage of loveless marital sex intercut with the brute, matter-of-fact stuffing of a turkey – a self-conscious comment on an act Findlay always claimed she resented having to film. Typically these movies were shot over a couple of days for a few thousand dollars, but even so images like these retain a stark quality and visual directness that defies easy description.

Any fair appraisal of Findlay’s work must thus contend with the contradictions of her life and artistic output. Hers are films often in the same breath crassly commercial and artistically ambitious, filled with sex and yet depressing and unerotic, shamefully exploitative and yet sensitive to the inner lives of the women who populate them. And her sheer industriousness – producing several films a year throughout the 1970s and up to the late ‘80s – makes her a rather remarkable figure, since few women had the opportunity to direct as many films in that era, least of all exploitation films. It’s therefore easy to imagine that the ongoing recovery, restoration, and revival of her work on Blu-ray – released by Vinegar Syndrome, which got access to an archive of prints sealed behind a wall in a warehouse – make her an irresistible target of feminist reclamation. In 2023, she received her first critical study in book form, the excellent and long overdue academic anthology ReFocus: The Films of Roberta Findlay, edited by Peter Alilunas and Whitney Strub for the Edinburgh University Press. That book is a welcome reevaluation of and deep dive into this filmmaker’s multitudinous body of work, and its authors are clearly sensitive to many of the frustrations her films provoke and the abiding issues they raise. They also willingly play the foil to Findlay’s own incredulity. Since she still claims to be aghast at the idea that anybody would ever take her films seriously, they do exactly that, and with an intellectual rigour that for the most part steers clear of excessive academicism. Indeed, the extended interview that closes the volume is aptly and dryly titled, Roberta Findlay vs. Porn Studies.

Any fair appraisal of Findlay’s work must thus contend with the contradictions of her life and artistic output. Hers are films often in the same breath crassly commercial and artistically ambitious, filled with sex and yet depressing and unerotic, shamefully exploitative and yet sensitive to the inner lives of the women who populate them. And her sheer industriousness – producing several films a year throughout the 1970s and up to the late ‘80s – makes her a rather remarkable figure, since few women had the opportunity to direct as many films in that era, least of all exploitation films. It’s therefore easy to imagine that the ongoing recovery, restoration, and revival of her work on Blu-ray – released by Vinegar Syndrome, which got access to an archive of prints sealed behind a wall in a warehouse – make her an irresistible target of feminist reclamation. In 2023, she received her first critical study in book form, the excellent and long overdue academic anthology ReFocus: The Films of Roberta Findlay, edited by Peter Alilunas and Whitney Strub for the Edinburgh University Press. That book is a welcome reevaluation of and deep dive into this filmmaker’s multitudinous body of work, and its authors are clearly sensitive to many of the frustrations her films provoke and the abiding issues they raise. They also willingly play the foil to Findlay’s own incredulity. Since she still claims to be aghast at the idea that anybody would ever take her films seriously, they do exactly that, and with an intellectual rigour that for the most part steers clear of excessive academicism. Indeed, the extended interview that closes the volume is aptly and dryly titled, Roberta Findlay vs. Porn Studies.

Born Roberta Hershkowitz in 1943, over the course of two decades she was responsible in one way or another for almost 40 feature films, which she made under a variety of pseudonyms – “Anna Riva” and “Robert W. Norman” being two key ones – as well as under her married name, Findlay. She lent her services as actress and cinematographer to many other films, while for her own work she often acted as director, producer, screenwriter, and editor. Adding to the confusion, at various stages of her career, Findlay collaborated with men with their own artistic ambitions, such as husband Michael (who regularly directed his own films until he was decapitated by helicopter blades on top of the PanAm building in New York City in 1977), producer Allan Shackleton (who later physically abused her), and long-term partner and music producer Walter Sear, with whom she lived and worked until his death in 2010. In each case, the DNA of Findlay’s artistic vision would alter somewhat with the pull of their respective influences, and as several authors in the book stress, her work can be roughly structured along these lines: early films with Michael, independent hardcore films (often produced with Shackleton), hardcore films with Sear, and then finally horror films, also with Sear (Derek Gaskill, in his chapter in the book on Findlay, delves into some of the distinctions between her work before meeting Sear and after).

In a perverse way, critically engaging with Findlay’s work and accounting for the many transformations of her career parallels the considerations one must keep front of mind when grappling with the work of many of the great female filmmakers from film history, in distinct but related ways. Many women who started making movies before 1970 often did so in tandem with male artists – usually husbands or partners – whose authority granted them entrance, by accident or on purpose, into a world dominated by men. Their careers were thus often intertwined with that of a more famous man, existing in their shadow to one degree or another. This was the case with filmmakers as diverse as Yuliya Solntseva, who continued to realise films conceived by her husband Oleksandr Dovzhenko after he died, or Barbara Loden, whose output as a director was long eclipsed by that of her domineering husband, Elia Kazan, who discouraged her venture behind the camera. Ida Lupino stepped into the director’s chair for Not Wanted (1949), produced for her newly-registered production house, only when director Elmer Clifton had a blood clot in his brain three days into filming, and Kinuyo Tanaka got her break only when Mikio Naruse and Yasujiro Ozu intervened to grant her access to a men’s world; one film, The Moon Has Risen (Tsuki wa noborinu, 1955), was actually made from an unrealised Ozu screenplay. Like these other pioneering female filmmakers, Findlay’s path to directing was highly contingent and not always easy to trace; indeed, even landing on a precise date for her start as a director is not easy. She began making exploitation roughies – as cinematographer and often as star – around 1964, with Michael, who she met in college when she, a 16-year-old classically-trained pianist, offered her services as musical accompaniment to the silent masterpieces by Eisenstein and Griffith that he was showing at his film club. She features or even stars in his first films, including the Flesh trilogy (1966-68), and the authorship remains murky. She has claimed in the years since to have had little to do with films like Take Me Naked (1966) beyond starring in them, and yet in that particular case, the opening credits name her (as “Anna Riva”) as co-director. Despite her insistence that she had little to do with those films, a work like Take Me Naked does seem like a fusion of Roberta and Michael’s warring sensibilities, one more prosaic and artistic and the other more unfiltered and disturbing.

A few years later, she left Michael – whom she described as a psychopath who would have killed women if he wasn’t preoccupied making films – and started to direct movies alone. Her Angel Number 9 (1974), about a misogynist who is run down in the street, goes to heaven, and is sent back to earth in a woman’s body to learn his lesson one sexual humiliation at a time, was marketed in the press and on marquees as a curio: a hardcore film directed by a woman. In those days, there were talented women making exploitation films and softcore cheapies – most notably Stephanie Rothman and Doris Wishman – but as the ReFocus volume points out,[3] there were few women who were regularly making X-rated films for the commercial market besides Findlay (actress/director Lina Romay did so in Spain, with her husband Jesús Franco, and Charlene Webb and Ann Perry made a handful of films during this period, though nothing close to Findlay’s output). Yet even this public, entrepreneurial self-consciousness about her own significance as a female exploitation filmmaker was not consistent and also proves difficult to pin down. The next year, Anyone But My Husband, another scathing film about male lechery and female pleasure, was signed by “Robert W. Norman”, as was her most famous and probably best hardcore film, A Woman’s Torment (1977), which takes place entirely in a beach house that recurs in several Findlay films (due to its apparent convenience as a location). Despite the filmmaker’s overt, even performative public misogyny when speaking about women, in both Findlay films there is an evident focus on the protagonists’ pleasure, their delight in creatively exploring their sexuality for the first time. Coupled with the fact that all the men are portrayed as clowns at best or predators at worst, this does suggest something of where Findlay’s sympathies ultimately lie. On most of her films, she proudly retained her credit as cinematographer, the area – along with editing – that she will begrudgingly admit to having some interest in and holding some pride for.

Like a lot of hardcore directors, Findlay’s work tapered out by the mid-1980s when the advent of video decimated the market for pornography. For somebody for whom both making money through rentals and lighting for 35mm were always the two major appeals of making movies, the transition to video signalled a definitive break. Before leaving pornography for good, Findlay made Shauna: Every Man’s Fantasy in 1985, a vile pseudo-documentary made to cynically cash-in on the then-recent suicide of 20-year-old adult film star Shauna Grant, recycling outtakes of her sex scenes from Glitter (1983) and Private Schoolgirls (1983), two earlier films with Findlay, and mixing them with on-camera interviews with other porn stars (some real, some staged), who also have sex on camera in between the discussions. Though fascinating, that is an indefensible piece of work, especially when the narrator – played by Cinema Blue editor Joyce James, who was supposedly hoodwinked into appearing in the film under false pretences by Findlay – states that “Whatever problems [Shauna Grant] had were her own. They would have eventually destroyed her whatever profession she pursued.”

Scholar Kier-La Janisse discusses this bizarre and disturbing film at length in her chapter in ReFocus: The Films of Roberta Findlay, one of its most commendable and imaginative in the whole volume. Hers is not a defence of Findlay making Shauna: Every Man’s Fantasy, but she does illuminate the film’s odd avant-garde qualities as a ghoulish and exploitative work of docu-fiction. In so doing, she shows how one can seriously contend with these films intellectually and emotionally without pigeonholing their director. There are parts, particularly towards the beginning, where this key Findlay film has something resembling “productive tension” in its play with fiction and staged footage, as when one porn star pretends to be a producer who worked with Shauna earlier in her career. But it remains a film that is impossible to pin down, an open-ended work that both entices and frustrates well-meaning auteurist readings. In the interview that closes the book, editors Peter Alilunas and Whitney Strub ask Findlay about it and, faced with the prospect that she made a really evil piece of exploitation, the director basically shrugs it off without getting too introspective. “Wasn’t that awful?” she laughs.

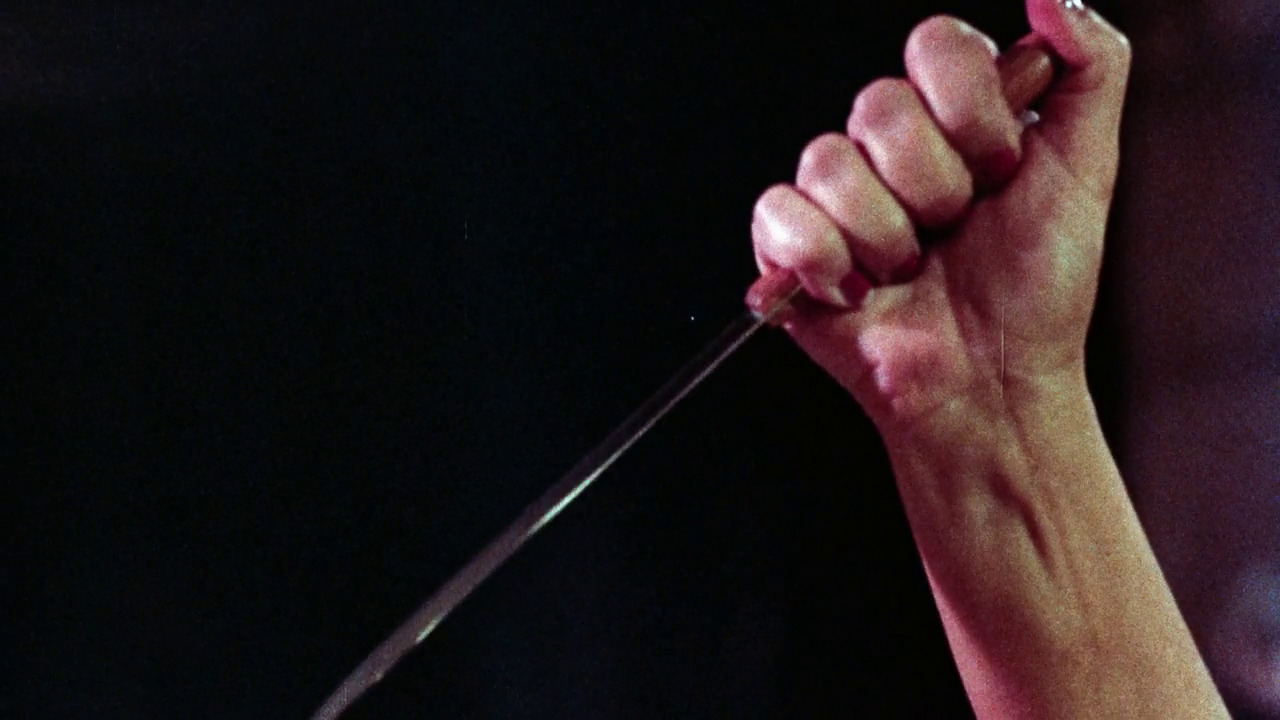

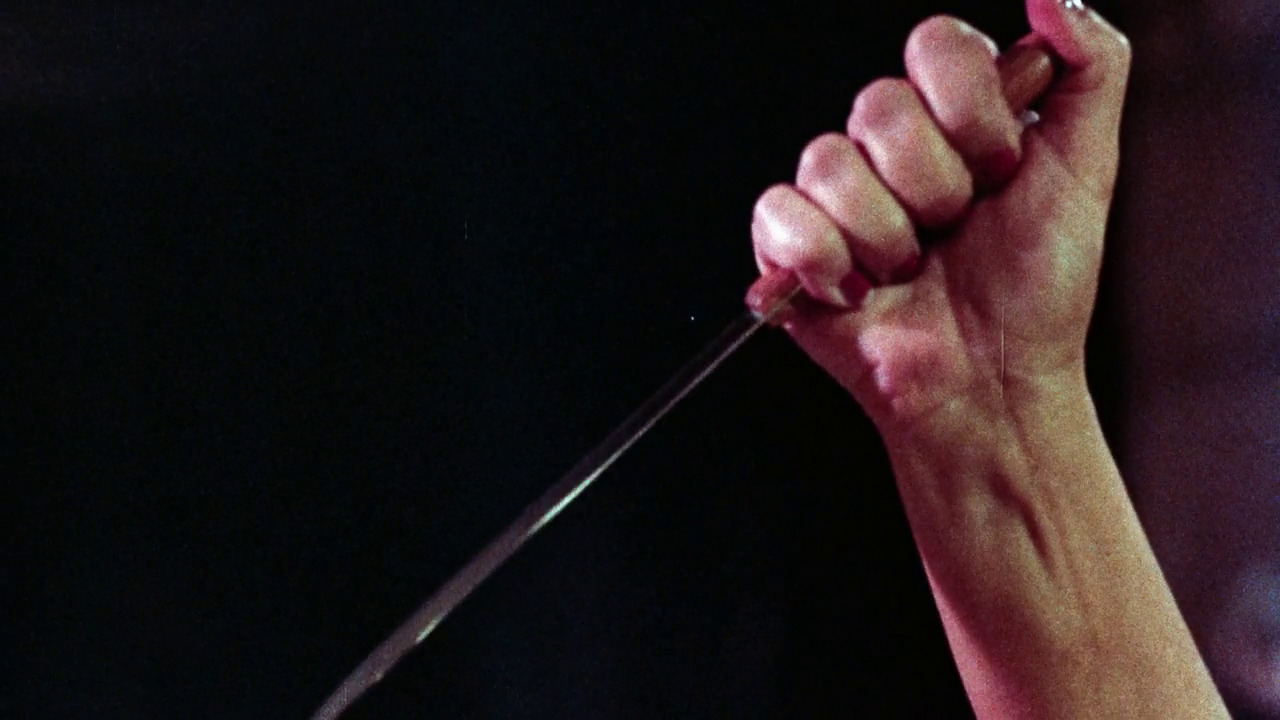

Even the biggest Findlay fan must admit: these are not easy movies to love. They are dark and misanthropic in the extreme. They contain a good deal of uncomfortable sex and prod uneasily at the uglier aspects of two people engaging in sex together. Violence has a powerful, discomfiting force in her films, as when a woman is brutally raped with a broom handle in Tenement (1985), an act Findlay films in all its salacious detail, or in the delirious scenes of a mentally ill woman being raped and then taking bloody revenge in A Woman’s Torment. These tensions in her films suggest that “Roberta Findlay” is an incoherent construction, a collection of disparate odds and ends that are often at odds with the whole, but which nevertheless remain sui generis in film history. As the contributors in the new book demonstrate, it is up to her admirers to build systems that account for everything that flows through these beguiling, singular, impossible-to-shake-off films from an overlooked and understudied historical moment.

A version of this text also appears in Outskirts Film Magazine Nº3.

Proofreading: Zuzana Hrivňáková

Notes:

[1] ed. ALILUNAS, Peter. STRUB, Whitney. ReFocus: The Films of Roberta Findlay. Edinburgh University Press, 2023, pp. 2.

[2] For a more lengthy discussion, read Finley Freibert’s chapter Singularity and Conformity: Feminism and Roberta Findlay’s Strategic Marketing Communications in the same volume, pp.26-39.

[3] See Jennifer Moorman and Derek Gaskill’s chapters in the book for more detail.

Pictures:

[1, 4, 5, 7] A Woman’s Torment (Roberta Findlay)

[2 – 3] Snuff (Roberta Findlay)

[6] Anyone But My Husband (Roberta Findlay)

Trigger warning: following text contains a representation of sexual violence.

Between 1966 and 1989, Roberta Findlay directed, wrote, produced, shot, edited, and occasionally acted in countless exploitation, horror, and pornographic films, often under pseudonyms or in production contexts where the precise nature of her involvement was unclear (and subsequently obfuscated by Findlay’s own shifting stories on the subject). At her company Reeltime, she also managed the distribution of many of these works across North America and, at least to some extent, in foreign territories, first for her adult work and then, between 1985 and 1988, for the cheap horror and exploitation films she made with the VHS market in mind. Despite this considerable and quite singular oeuvre, Findlay remains an elusive character whose films and pugnacious public comments thwart the tidy auteurist and especially feminist readings well-meaning fans apply to them.

As Findlay is happy to brutishly insist whenever anybody asks, she was a commercial opportunist who only made “dirty movies” because they were fast and cheap and because she wanted to make as much money as quickly as possible. She will admit she took a measure of pride in her lighting and editing, but otherwise stresses that she only made the films for cash and gave up on the business as soon as they ceased to turn a profit. She hated shooting sex scenes, reportedly giving such pithy on-set direction as “Okay, everybody screw”.[1] She insisted that she always refused to hire women for her films because of their apparent physical (and mental) weakness, despite once working as cinematographer on Karen Sperling’s pioneering feminist film The Waiting Room (1973),[2] whose crew consisted entirely of women two years before Chantal Akerman insisted on the same for Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). She continues to scorn anybody who watches her films today as “sick” and is known for hanging up on interviewers who try to contact her. But she was also trained as a classical pianist before she left home at 16 to make films with Michael Findlay, of whom her Hungarian-Jewish immigrant parents disapproved, and has repeatedly said that her dream project is an adaptation of Herman Melville’s Pierre; or, The Ambiguities (1852). And there are crucial moments in her films when her personality – sardonic but artistically ambitious – is unmistakably evident: Mystique (1980), a mournful X-rated film about a dying woman seduced, brutalised, and humiliated by a much younger female lover, opens with a poem by Paul Valéry, while Anyone But My Husband (1975) begins with a montage of loveless marital sex intercut with the brute, matter-of-fact stuffing of a turkey – a self-conscious comment on an act Findlay always claimed she resented having to film. Typically these movies were shot over a couple of days for a few thousand dollars, but even so images like these retain a stark quality and visual directness that defies easy description.